Developing Better Kidney Disease Models in Microgravity

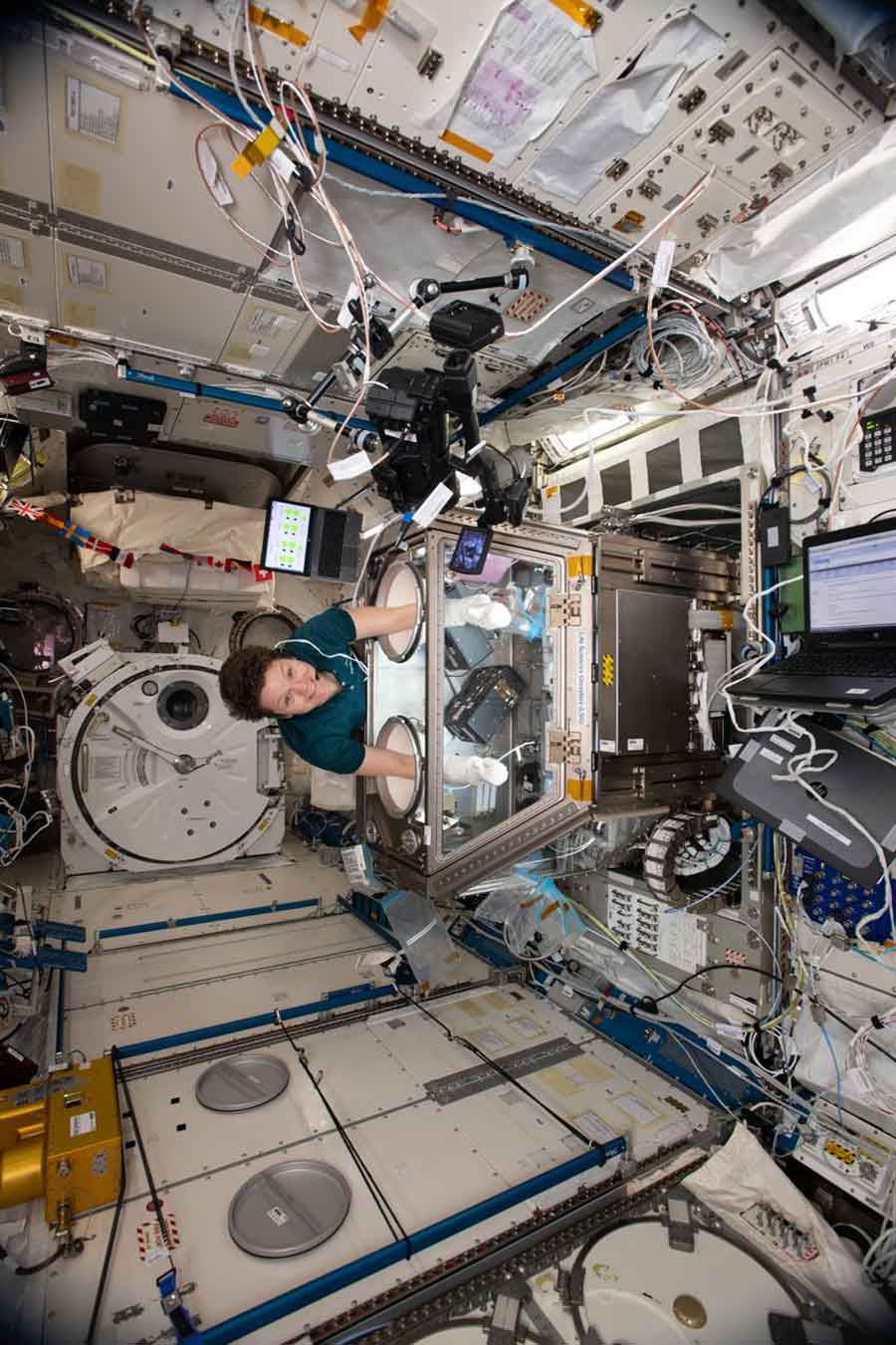

NASA astronaut Christina Koch works on the University of Washington kidney tissue chip investigation inside the Life Sciences Glovebox onboard the ISS.

Media Credit: NASA

March 30, 2020 • By Amelia Williamson Smith, Staff Writer

March is National Kidney Month, a time dedicated to raising awareness about kidney health. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that 15 percent of adults in the United States—more than 37 million people—have chronic kidney disease. Moreover, 9 out of 10 people with chronic kidney disease are unaware they have it and find out only after irreversible damage to their kidneys.

Thus, National Kidney Month is also a time to raise awareness about the importance of research to help improve the prevention and treatment of kidney disease. In addition to research taking place in labs around the world, valuable kidney disease research is also being done on our nation’s only lab off this world—the International Space Station (ISSInternational Space Station) U.S. National Laboratory.

At the 2019 ISS Research and Development Conference, University of Washington School of Pharmacy researcher Cathy Yeung discussed her team’s research using a kidney-on-a-chip system onboard the ISS National Lab. By studying kidney function in space, Yeung and her team hope to gain valuable information to help people with kidney disease back on Earth.

“We hope to understand how kidney disease starts and to define the biochemical signatures of the very early stages of kidney disease,” Yeung said in her 2019 ISSRDC(Abbreviation: ISSRDC) The only conference dedicated exclusively to showcasing how the International Space Station is advancing science and technology and enabling a robust and sustainable market in LEO. This annual conference brings together leaders from the commercial sector, U.S. government agencies, and academic communities to foster innovation and discovery onboard the space station. ISSRDC is hosted by the Center for the Advancement of Science in Space, manager of the ISS National Lab; NASA; and the American Astronautical Society. talk. “If we can figure these signals out, we can develop tests [for earlier diagnosis] to give a person time to modify their health behaviors, adjust their diet, and maybe start them on medication that might be protective for their kidneys.”

Tissue Chips in Space

Yeung’s ISS National Lab research was awarded through the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) Tissue Chips in Space initiative. Tissue chips are small devices that contain human cells grown on an artificial scaffold to model the detailed physical structure and function of human tissue.

In 2016, NCATS, which is part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), announced a four-year collaboration with the ISS National Lab to support the use of tissue chipA tissue chip, or organ-on-a-chip or microphysiological system, is a small engineered device containing human cells and growth media to model the structure and function of human tissues and/or organs. Using tissue chips in microgravity, researchers can study the mechanisms behind disease and test new treatments for patients on Earth. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) has a multiyear partnership with the ISS National Laboratory® to fund tissue chip research on the space station. technology for translational research onboard the ISS to benefit human health on Earth. In December 2017, the ISS National Lab, NCATS, and the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB)—also part of NIH—announced a second funding opportunity supporting tissue chip research in space.

Studying Early Kidney Disease

Most people know that the kidneys filter drugs and toxins from the body and produce urine, but the kidneys are also responsible for many other critical bodily functions. The kidneys help regulate blood pressure and produce hormones that promote red blood cell production. They also maintain the body’s acid, base, and water balance and play an important role in maintaining bone health by activating vitamin D in the body.

Kidney failure affects almost every system in the body, underscoring the importance of maintaining kidney health. However, it is difficult to detect kidney disease in the early stages—current diagnostic tests do not appear abnormal until about half of the nephrons in a person’s kidneys are damaged.

Close-up of the kidney-on-a-chip system

Media Credit: Alex Levine, UW School of Pharmacy

Improved disease models are needed to better understand the early stages of kidney disease and design better diagnostic tests.

Although rodent and 2D cell culture models are useful, they do not fully replicate conditions in the human body. To provide a better model, Yeung and her team developed a 3D microfluidic model called a “kidney-on-a-chip.” This system, about the size of a credit card, allows the researchers to grow human kidney cells into tubular formations under a constant flow—an environment that more closely mimics how kidney cells grow in the body.

Taking Kidney-on-a-Chip to Space

NASANational Aeronautics and Space Administration astronaut Anne McClain works on Kidney Cells hardware onboard the ISS.

Media Credit: NASA

MicrogravityThe condition of perceived weightlessness created when an object is in free fall, for example when an object is in orbital motion. Microgravity alters many observable phenomena within the physical and life sciences, allowing scientists to study things in ways not possible on Earth. The International Space Station provides access to a persistent microgravity environment. induces rapid changes in body systems, and spaceflight studies can provide accelerated models of disease. In their first ISS National Lab investigation, which launched on SpaceX’s 17th commercial resupply mission last year, Yeung and her team used their kidney-on-a-chip to examine kidney structure and function in microgravity.

“This [research] can help us understand the dysregulation of the kidney in microgravity,” Yeung said in her 2019 ISSRDC talk. “But more importantly, it can help us understand the sentinel events in the development of kidney disease in the general population. In this sense, we’re using the microgravity environment as a kidney disease accelerator to trigger the very earliest events in the transition from kidney health to kidney disease.”

The team plans to launch a second kidney-on-a-chip investigation to the ISS National Lab next year to model kidney stone formation. To do this, the team will flow a solution containing microcrystals of calcium oxalate through the kidney-on-a-chip. On Earth, gravity causes these microcrystals to settle, leading to a nonuniform exposure of kidney cells to the microcrystals. However, in microgravity, the microcrystals remain suspended in the solution, providing a more even distribution and exposure.

According to the National Kidney Foundation, an estimated one out of every ten people will have a kidney stone at some point in their lives—and each year, more than half a million people go to the emergency room for problems related to kidney stones. Results from Yeung’s research could shed light on new ways to prevent and treat kidney stones to improve quality of life in patients on Earth.

Learn more about Yeung’s kidney-on-a-chip research in the below video from the University of Washington and in the ISS360 article “Kidney Tissue Chips in Space: Opportunities and Challenges.”